November 13, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

"In June 1953, North American initiated an in-house study of advanced F-100 designs, leading to proposed interceptor (NAA 211: F-100BI denoting "interceptor") and fighter-bomber (NAA 212: F-100B) variants. Concentrating on the F-100B, the preliminary engineering and design work focused on a tactical fighter-bomber configuration, featuring a recessed weapons bay under the fuselage and provision for six hardpoints underneath the wings. Single-point refuelling capability was provided while a retractable tailskid was installed. An all-moving vertical fin and an automated flight control system was incorporated which permitted the aircraft to roll at supersonic speeds using spoilers. The flight control system was upgraded by the addition of pitch and yaw dampers.

The aircraft's most distinguishing feature is its dorsal-mounted variable-area inlet duct (VAID). While the VAID was at the time a system unique to the F-107A, it is now considered to be an early form of variable geometry intake ramp which automatically controlled the amount of air fed to the jet engine. Although the preliminary design of the air intake was originally located in a chin position under the fuselage (an arrangement later adopted for the F-16), the air intake was eventually mounted in an unconventional position directly above and just behind the cockpit.The VAID system proved to be very efficient and NAA used the design concept on their A-5 Vigilante, XB-70 Valkyrie and XF-108 Rapier designs.

The air intake was in the unusual dorsal location as the USAF had required the carriage of an underbelly semi-conformal nuclear weapon. The original chin intake caused a shock wave that interfered in launching this weapon. The implications this had for the survivability of the pilot during ejection were troubling. The intake also severely limited rear visibility. Nonetheless this was not considered terribly important for a tactical fighter-bomber aircraft, and furthermore it was assumed at the time that air combat would be via guided missile exchanges outside visual range.

In August 1954, a contract was signed for three prototypes along with a pre-production order for six additional airframes."

↧

November 13, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

↧

November 14, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

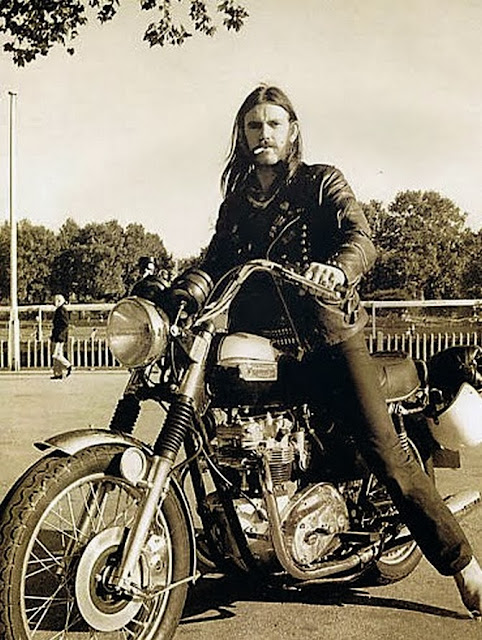

"The Triumph T140V Bonneville is a great rideable classic and is much more affordable than its earlier counterparts.

The Seventies were not good years for Triumph. By 1972 Triumph, arguably the personification of motorcycles and motorcycling, had been eclipsed by a hoard of Asian upstarts, despite 70 years of manufacturing tradition behind the fabled company.

In some ways, Triumph had been its own worst enemy. An entrenched, misplaced belief within the British motorcycle industry in its own superiority had resulted in outdated product, just as new rivals were launching the most technologically exciting motorcycles ever seen. Honda, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Yamaha were spearheading a revolution, changing and innovating their products yearly. But in 13 years of production, Triumph’s iconic Bonneville, introduced to rave reviews in 1959, had changed little. At Triumph, it appeared that evolution, not revolution, was the order of the day.

The Bonneville desperately needed a shot in the arm to remain competitive, and Triumph belatedly responded in 1973 by upping the Bonnie’s 650cc engine to 744cc and, finally, fitting a five-speed transmission in place of the old four-speed.

Unfortunately, the “new” Bonnie, dubbed the T140V, suffered under Triumph’s heavy load. That same year, Triumph announced the closure of the Meriden plant where the Bonnie was built, prompting the workforce there to wage an 18-month strike, during which all Bonneville production ceased.

This could have been the end of Triumph, and the company’s future looked bleak at best. But new hope came in the spring of 1975, when the striking workers formed the Meriden Cooperative. With loans from the government, the new company renewed production of the Triumph T140V Bonneville.

The great Triumph twin got a new lease on life, as once again new T140Vs started rolling off the assembly line.

Unlike its former stewards, the Meriden Cooperative saw the need to update and improve the Bonnie, while at the same time playing to its time-honored strengths of simplicity, agility and light weight.

The new Bonnie benefited from a fresh imperative to improve the breed. Oil leakage, always the scourge of British twins, was profoundly tamed, and the Triumph T140V Bonneville was continuously improved and updated.

Front and rear disc brakes came in 1976, as did left-hand shift to satisfy U.S. regulations. Much-improved Amal MkII carburetors came in 1978, and by 1979 all Bonnies sported electronic ignition."

↧

November 14, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

November 15, 2013, 4:00 am

↧

↧

November 15, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

"This machine is one of the last pair of Manx Nortons owned and campaigned by the legendary tuner/entrant Francis Beart. In 1966 this bike, together with a 500cc Manx, had been ridden by Joe Dunphy in the Isle of Man TT shortly before the Manx Grand Prix (earlier than normal that year due to the seamen's strike). Dunphy recorded DNFs on both machines, which were ridden in the Manx Grand Prix that year by Keith Heckles. Heckles finished 2nd in the Junior race on this 350 behind George Buchan, averaging 92.03mph.

The following year Heckles was again entered by Beart in both the Senior and Junior Manx Grand Prix events. After both bikes went well in practice, the 500, after breaking the lap record twice, retired on the 4th lap. In the Junior event, Heckles, on this bike, was leading the race on the 2nd lap. After a stop for fuel at the end of the 2nd lap, Heckles dropped down the order but retook the lead on the 5th lap, only to stop on the final lap after running out of fuel. He scrounged some petrol from another competitor and managed to finish the race, albeit in 42nd place.

Following the race, Beart sold both machines (350 and 500) for the princely sum of £1,000 to Hector Dugdale, the well-known Cheshire dealer/entrant, who in turn sold on the 350 to a Liverpudlian named Alan Prange. Prange raced it at only a few local meetings before passing the bike on to Heckles' sponsor at the time, Bob Vincent from Wigan, enabling Heckles to race the machine again. He entered a few races at Aintree and Oulton Park, and competed in the 1969 Junior TT, finishing 11th at an average speed of 90mph.

When Bob Vincent died, Keith Heckles bought the bike from his widow around 1972. He did not race the Manx very often after that, but did loan it to his good friend Frank Steele to race in the Manx Grand Prix in 1976, possibly its final race. Keith subsequently sold the 350 to the well-known North-of-England Norton collector Eric Biddle. A few years later, Biddle sold the Norton to Mike Steele of Leeds. Mike Steele carried out some restoration work, calling on Keith Heckles to overhaul the motor for him (see 1994 Classic Motorcycling Legends article on file) and paraded the bike occasionally.

During 1996 Steele was approached by Patrick Godet, who was restoring the 1967 Beart 500 Manx for Jean-Christophe Ollieric, a Parisian enthusiast. Godet needed an original Jakeman fairing to copy for the 500, and asked Mike Steele if he could borrow the 350's fairing in order to make a pattern. During the course of discussions it transpired that Steele was prepared to part with the bike, and it was duly purchased by Ollieric in 1996."

↧

November 15, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

November 16, 2013, 9:00 am

↧

November 16, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

↧

November 17, 2013, 9:00 am

↧

November 17, 2013, 11:00 am

Around Australia The Hard Way in 1929 is a true adventure of two young men from Sydney who travelled Australia by motorbike, a 7/9hp magneto model Harley Davidson.

↧

November 20, 2013, 4:12 am

↧

November 20, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

"The Hughes XF-11 was a prototype military reconnaissance aircraft, designed and flown by Howard Hughes for the United States Army Air Forces. Although 100 F-11s were ordered in 1943, only two prototypes and a mock-up were completed. During the first XF-11 flight in 1946, Howard Hughes crashed the aircraft in Beverly Hills, California. The production aircraft had been cancelled in May 1945, but the second prototype was completed and successfully flown in 1947. The program was extremely controversial from the beginning, and the F-11, along with the Hughes H-4 Hercules flying boat, was investigated by the U.S. Senate in 1947–1948.

While Hughes had designed its predecessors to be fighter variants, the F-11 was intended to meet the same operational objective as the Republic XF-12 Rainbow. Specifications called for a fast, long range, high-altitude photographic reconnaissance aircraft. A highly modified version of the earlier private-venture Hughes D-2 project, in configuration the aircraft resembled the World War II Lockheed P-38 Lightning, but was much larger and heavier. It was a tricycle-gear, twin-engine, twin-boom all-metal monoplane with a pressurized central crew nacelle, with a much larger span and much higher aspect ratio than the P-38's wing.

The XF-11 used Pratt & Whitney R-4360-31 28-cylinder radial engines. Each engine drove a pair of contra-rotating four-bladed, controllable-pitch propellers, which can increase performance and stability, at the cost of increased mechanical complexity. Due to constant problems with the contra-rotating propulsion system, the second prototype had regular four-bladed propellers.

On the urgent recommendation of Colonel Elliott Roosevelt, who led a team surveying several reconnaissance aircraft proposals in September 1943, General Henry "Hap" Arnold, chief of the U.S. Army Air Forces, ordered 100 F-11s for delivery beginning in 1944. In this, Arnold overrode the strenuous objections of the USAAF Materiel Command, which held that Hughes did not have the industrial capacity or proven track record to deliver on his promises. (Materiel Command did succeed in mandating that the F-11 be made of aluminum, unlike its wooden D-2 predecessor.) Arnold made the decision "much against my better judgment and the advice of my staff" after consultations with the White House. The order was cancelled on 29 May 1945, but Hughes was allowed to complete and deliver the two prototypes.

Numerous difficulties of both technical and managerial nature accompanied the program from the beginning. In 1946-1948, the Senate subcommittee to investigate the Defense Program, popularly known as the Truman Committee and then the Brewster Committee, investigated the F-11 and H-4 programs, leading to the famous Hughes-Roosevelt hearings in August 1947.The program cost the federal government $22 million.

The first prototype, tail number 44-70155, piloted by Hughes, crashed on 7 July 1946 while on its maiden flight from the Hughes Aircraft Co. factory airfield at Culver City, California.

Hughes did not follow the agreed testing program and communications protocol, and remained airborne almost twice as long as planned. An hour into the flight (after on-board recording cameras had run out of film), a leak caused the right-hand propeller controls to lose their effectiveness and the rear propeller subsequently reversed its pitch, disrupting that engine's thrust, which caused the aircraft to yaw hard to the right. The USAAF account noted that "It appeared that loss of hydraulic fluid caused failure of the of pitch change mechanism of right rear propeller. Mr. Hughes maintained full power of right engine and reduced that of left engine instead of trying to fly with right propeller windmilling without power. It was Wright Field's understanding that the crash was attributed to pilot error."

Rather than feathering the propeller, Hughes performed improvised trouble-shooting (including raising and lowering the gear) during which he flew away from his factory runway. Constantly losing altitude, he finally attempted to reach the golf course of the Los Angeles Country Club, but about 300 yards short of the course, the aircraft suddenly lost altitude and clipped three houses. The third house was completely destroyed by fire, and Hughes was nearly killed. The crash is dramatized in the 2004 film The Aviator.

The second prototype was fitted with conventional propellers and flown by Hughes on 5 April 1947, after he had recuperated from his injuries. Initially, the USAAF had insisted that Hughes not be allowed to fly the aircraft, but after a personal appeal to Generals Ira Eaker and Carl Spaatz, he was allowed to do so against posting of $5 million in security.

This test flight was uneventful and the aircraft proved to be stable and controllable at high speed. It lacked low-speed stability, however, as the ailerons were ineffective at low altitudes. When the Army Air Forces (AAF) evaluated it against the XF-12, testing revealed the XF-11 was harder to fly and maintain, and projected to be twice as expensive to build. A small production order of 98 for the Republic F-12 had been issued, but the AAF soon chose the RB-50 Superfortress, and Northrop F-15 Reporter instead, both of which had similar long-range photo-reconnaissance capability and were available at a much lower cost.

The F-12 production order was cancelled. When the United States Air Force was created as a separate service in September 1947, the XF-11 was redesignated the XR-11. The surviving XR-11 prototype arrived at Eglin Field, Florida, in December 1948 from Wright Field, Ohio, to undergo operational suitability testing through July 1949 but a production contract for 98 was cancelled. The airframe was transferred to Sheppard AFB, Texas, on 26 July 1949 for use as a ground maintenance trainer by the 3750th Technical Training Wing, and was dropped from the USAF inventory in November 1949"

↧

↧

November 20, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

November 21, 2013, 4:20 am

↧

November 21, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

![]()

![]()

"According to Dick Dale, he and his cousin were riding motorcycles to the beach on the Balboa Peninsula in southern California, where Dale befriended the local surfers. There he also began playing with a band at a club called the Rinky Dink. Another guitar player showed him how to make certain adjustments to the pickup settings on his Stratocaster guitar to create different sounds, and that sound, aided by other sonic developments and featuring Dale’s staccato attack, became his trademark. Although he was still playing country music, he moved closer to the beach and began surfing during the day and playing music at night, adding rock ‘n’ roll to his repertoire.”

“I do not play to musicians. I play to the people. I’ve never taken a lesson in my life, and I can play every instrument there is. I play by ear, but I can fool anybody into thinking I went to some conservatory of music. I create a nonchemical river of sound, and I never know what I’m playing next or how I’m going to play it. I just start ripping and take what I feel from the audience–and it comes. There’s no bullshit. If you’re not sweating, you’re stealing people’s money. That’s why people feel what I do. In all these years, I’ve never had one person walk out of a show and say, ‘Dick Dale’s a fake,’ or, ‘He sucks.’ One and one is two with Dick Dale. It’s not three, like these politicians say. The kids who’ve been following me around on this tour call my music `Dick Rock,’ and they call themselves `Dickheads.’ And the reason they do that is because music is an attitude–and man, my whole life has been an attitude, too.”

“I loved country music, and I always wanted to be a cowboy singer. So I followed people like Hank Williams and things like that. And in fact I even tutored Chet Williams’ daughter on how to be on stage. I’ve gotten to perform in the same building at the same time as people like Johnny Cash, Tex Ritter, Gene Autry, and Lefty Frizzell. I just did a memorandum song for Joe Maphis, who’s the father of the double-neck guitar. And at the same time it was Larry Collins and his sister Laurie, and I was sweet on Laurie at the time. And Larry, he was just a little kid, but could he play the double-neck guitar, because he was tutored by Joe Maphis. Larry was the one who taught me my first guitar lick. So anyway I did a dedication song they asked me to do on a thing called ‘Joe Maphis: Joe Maphis’ [?], it was a dedication to him, on his album that they did, they took all his old songs, he’s been passed on now. So I did that. And I just did one for Glen Campbell, because he used to play the backup guitars for me when I recorded with Capitol Records. He was one of the most incredible guitarists that could play anything on a guitar, and stuff like that.

I came to California in 1954. Drums were my first instrument. I used to listen to the big band albums that my Dad would bring home, and that’s what got me to play the trumpet, like Harry James, Louis Armstrong, and stuff like that. And I’ve always been self taught. I used to bang on my mother’s flour pans as a drum listening to Gene Krupa, cans of sugar and stuff like that in the Depression days. My father would say, ‘Stop scratching your mother’s cans!’ That’s where I got all my rhythm, and being left-handed. So when I first got my first instrument, I was reading in a Superman comic magazine. It said sell X number of jars of our Noxzema Skin Cream and we’ll send you this ukulele. Well I’d be out there in the snow banging on doors at night, ‘Buy my Noxzema Skin Cream.’ I finally got the ukulele and it was made out of pressed cardboard or something, I was so disillusioned I smashed it in a trash can. Then I went in and took the Pepsi-Cola bottles and the Coke bottles in my little red wagon, went down and got six dollars. And I went to the music store and I bought my first six-dollar ukulele. It was plastic and it had screws going into the tuning pegs so they would stay in it. But the book didn’t tell me – ‘turn it the other way stupid, you’re left handed.’ I was holding it to strum with my left hand ’cause all the rhythm was there.

I used to try to figure it out and tape my fingers to the strings and stuff like that when I’d go to sleep at night, hoping that they’d stay there. So I’d play upside-down backwards. And that’s not, like Jimi Hendrix, I found Jimi when he was playing bass for Little Richard in a bar in Pasadena to 30 people. He wasn’t Jimi Hendrix then. But then he’d come and ask me, how I did what I was doing. He said, ‘How do you get that slide?’ I showed him all the slides and everything like that. In fact, Buddy Miles (Hendrix’s drummer) when he would open for me, used to stand on stage and say, ‘You know, there wasn’t a day didn’t go by that Jimi didn’t say he got his best shit from Dale.’ The thing is, Jimi played—because he was a left-hander, and he couldn’t play like I was playing because I was playing upside down backwards, so we set him up, got him a left-handed neck, where the neck of the guitar was strung so that a left-handed player could play it, the way you’d string your strings. He was a true left-handed player playing on a left-handed neck. I wasn’t, I was a left-handed person playing upside-down backwards on a right-handed neck.

Leo Fender, who become like a father figure to me, died laughing when he gave me a Stratocaster. He said, “Here play this,” because I went to him and said, ‘My name is Dick Dale, I’m a surfer, I got no money, can you help me learn the guitar?’ He handed me the guitar and I held it upside-down backwards and he almost fell off the chair laughing. And he never laughed, he was like Einstein.

I wanted to make my guitar sound like Gene Krupa’s drums. I wanted a big fat sound, in fact I always tell my drummers that I want them to build to build on double-floor toms, because of that jungle sound. That’s where Gene Krupa got all his rhythms from, from Natives. He always played on the one, what we call the one. Musicians play on the one-and.

So it goes like this; tika-tika-taka-tika-taka-tika-taka-tika-ta, and you learn this—I’ve been in the martial arts all my life, and the routine, and in the Shaolin temples I’ve been with monks. So in the Shaolin temple they never allow you to touch the skin of a drum with your hands until you can mouth what you’re going to play. And if you go back in time at the first orchestral symphonic performance of symphonies, you will hear/see the maestro standing on his podium with the baton in his fingers, and wave the wand, and he’ll be keeping time going 1234-1234-1234-123, it goes all the way back to there.

Gene Krupa, he watched the natives when they would go either into their war dances or their celebration dances or anything, and they’d be holding their shafts, the spears, and they would always dance to the rhythm, going chickachicka-chackachicka-chickachickaBOOM, chickachicka-chackachicka-chickachickaBOOM, like that, and that was always on the one. So when I play my music, I play it that way, I play it to the grassroots people that don’t count on the one hand. That’s why all ages from 5 years old up to 105 can understand what I’m playing and they can feel what I’m playing when they’ve got in their head keeping time to my music.

I wanted my guitar to sound big and fat and thick. Well in those days, in the 50s, they didn’t have an electronic piece of equipment that makes the sound sound that way, and it’s called a transformer. And transformers only favored highs mids, or lows, never all three. And I wanted Leo to try to accomplish that. And every time he’d bring in a wall of speakers in the little office where we used sit together, they would sound nice and loud. But when I’d get them on stage, then I’d fry them, they’d catch on fire. The reason why is because when you’re pushing amperage to something that can’t handle them, it heats up the coil, it heats up the wires in the speaker, and they start frying the cloth on the speaker, the paper. I was in the Royal Albert Hall in London, where the queen goes, and performing, and my bass player was going, ‘Dick, you’re smoking the speakers,’ and I said, ‘Shut up, just keep playing, it’s their PA system.’

Leo Fender saw me blow over 50 of his amplifiers and he kept having to remake them. Then he stood in front of me in the middle of 4,000 people and he said to his number-two man, Freddie—Tavares from Hawaii, who played Hawaiian steel guitar for Harry Owens, who did all the beautiful Hawaiian songs, he was the number two man, he was the man who perfected the Telecaster. I’m the guy who perfected the Stratocaster and made changes with Leo and stuff like that. We’d sit down together in his living room and listen to Marty Robbins on the little old Jansen 10-inch speaker, but I blew every one of those speakers. So what happened was he said, now I know what Dick’s trying to tell me, and went back to the drawing board. And going from a 15-watt output transformer that didn’t give you that, it gave you loud enough for a living room but not in an auditorium, because in the auditorium the people’s bodies would suck up the sound, the fatness of the sound.

From there Leo created the first 85-watt output transformer, which peaked 100 watts. Now going from a 10-watt, 15-watt output transformer to an 85-watt output transformer that peaked at 100 watts, that’s like going from a little VW bug to a Testarossa. That was the first breakthrough, splitting the atom, of music and evolving volume that you’re talking about. Now in order to get that volume, we needed that transformer; I also used instead of 6-7-8-9-10-gauge strings, my strings were 16-18-20 unwound, and 39-49-60-gauge wound. Critics called them telephone wires. I even experimented with piano strings on my guitar, on my Stratocaster.

But we needed a speaker that could handle it. So we went to JBL. We told them we wanted a 15-inch D130. We wanted a speaker that was 15 inches and had around an 11-pound magnet on the back. I wanted an aluminum dust cover in the middle of the column so I could hear the click of the pick. They started laughing and they were saying, ‘What are you trying to do, put it on a tugboat?’ Leo said, ‘If you want my business, make it.’ And they did, and it was called the 15-inch JBL D130. Now we took that and built a three-foot high cabinet, two feet wide, 12 inches deep, with no portholes at all, just the speaker hole, and we packed it full of fiberglass. And then we went and plugged it in to the Showman—he called it a Showman amplifier, because he called me a showman because I was always jumping up on top of my speakers, and rocking back and forth while I played, and rocking the speaker back and forth, and I’d do all kinds of crazy things, I’d leap off the stage and slide on my knees on the floor as I was ending a song, and he said, “Man, you’re a showman.” I wanted it to be the cream because one night we ran out of amplifiers and he had to make one fast, and he found some cream tolex ones in the back room and he covered it, and he said, ‘Don’t let anybody see it because they’re going to want it because you’re playing on it. But it’s very impractical, they’ll stain it with coffee and they’ll stain it with cigarette butts and everything else.’ And I said ‘Oh but I love it I love it.’ And the next day he calls me in and he shows me his crew is making them with the cream tolex. So there, that was another breakthrough.

The next breakthrough was, I wanted it to be fatter. And also, not only the thicker the gauge string was a fatter sound, but the thicker the wood of the Stratocaster, that’s why I was considered the best rock-and-roll guitar player. Because the wood is thick, and if you could put strings on a telephone pole with a pickup, you’d have the fattest sound in the world, but you can’t hold a telephone pole. So we trimmed off the back sides of the Stratocaster and made the wood really thick, which gave it a real chunky fat sound. So the strings, the output transformer, and the solidity of the wood, and the speaker, that made the sound that Dick Dale is famous for.

Then I wanted to put another speaker in it. So he flipped out, went back to the drawing board, and he had to change the ohms down to 4 ohms. Originally, the speaker on the back said 16 ohms, but it’s not, it’s 8 ohms. So he made the first next-step up 4-ohm output transformer to match the twin speakers. This was a 100-watt output transformer peaking 180 watts, using tubes, for a fat sound. And that was called a Dick Dale transformer.

I still gave trouble to the speakers, the single-speaker cabinet, because it was twisting, and the reason why it was twisting was because when I was picking on my string like Gene Krupa plays sticks on his drum, I was doing that on my string, I’m playing drums. And it was confusing the speaker and it was twisting and jamming. When you would rub the speaker back and forth with your finger, you’re supposed to hear nothing. But when it jams you’d hear ekk-ekk-ekk [laughs]. So we went back to Lansing and told them to rubberize the outside ridge, so that it would flex easier, and it did the trick. We used the same trick for the high cabinet, and I just put a divider in the middle.”"

↧

November 21, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

↧

November 22, 2013, 4:45 am

↧

November 22, 2013, 9:00 am

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

↧

November 22, 2013, 11:00 am

↧

.jpg)